WHAT HAPPENED WITH DANSKE BANK AND HOW IT CAN BE AVOIDED

A Small Branch With Generous Profits

Between 2007 and 2015, the Estonian branch of Danske Bank pipelined funds from Russia, Moldova and Azerbaijan, A large part of the funds worth €200 billion is believed to be associated to criminal activities, as well as to individuals appearing on sanction lists or involved in drugs and tax evasion.

Danske Bank took control of the Estonian bank following the acquisition of Finnish Sampo Bank in 2007. While the Estonian unit represents only 0.5% of Danske’s assets, its non-resident business accounted for 8% of the pre-tax profits. In 2008, the Russian Central Bank and Estonian regulators ordered the bank to investigate dubious operations within its Estonian branch. While the high level of suspicion regarding this unit’s activities was no longer a secret, funds kept being cleared in Estonia to reach a record amount of €32 billion in 2013 alone, with €8 billion transferred through what we call “mirror trades”.

The Bank Had Knowledge of its AML Failures

Six years after the takeover of the Estonian branch, Howard Wilkinson, a former top executive of the bank, revealed the case in an email titled “Whistleblowing Disclosure: knowingly dealing with criminals in Estonia branch”, sent to Estonian regulators.

Following the alert, Danske conducted an audit early 2014 in its Estonian branch. In its report, the investigating audit firm stated that they could not identify the sources of funds and the beneficiaries of the trades.

This led the bank to order the closure of its non-resident business, completed by 2016. For the record, this activity oversaw no less than 15,000 bank accounts with transactions mostly conducted in Euro or Dollars.

In March 2017, the daily Berlingske published a first investigation [1], where it looked at claims of money-laundering regarding “shady companies in tax havens”. The report pointed out the involvement of Danske Bank and Nordea in the laundering of funds of criminal source. According to the same report, while Nordea claimed tightening the rules and removed most of its suspicious customers, Danske Bank’s stance was that only the Estonian branch was problematic.

At that stage, even though reprimanded by the Danish financial regulator in May 2018, there were no actions taken against the bank’s management.

It didn’t take long before a 2013 meeting minutes were published by the Financial Times [2]; in this meeting, the chief executive Thomas Borgen declined calls to scale back the non-resident business in Estonia. As a consequence, he offered to resign and his mandate was terminated with immediate effect in October.

Heavy Consequences

Amid the scandal, the Chief Executive Officer is not the only one who lost his job. In addition to 10 of the bank’s former employees detained in December in Estonia, the board chairman, Ole Andersen, was also fired by Danske Bank’s main shareholders.

From a regulatory perspective, trouble comes all together. The Danish financial supervisor rejected the board’s nominee to replace Mr.Borgen, for lack of experience, and this is not over yet. In addition to the investigation reopened by the same regulator, extra-national bodies are currently addressing the issue. The EU commissioner for justice, Věra Jourová, urged ministers from Denmark and Estonia to explain the failure of executives and regulators to prevent the scandal, a call to which the Danish PM promised further action against the bank and its executives. Note also that the Danish parliament voted a very consequential increase in the maximum fines for money laundering, a raise that may not be applied retrospectively to Danske. Moreover, the probe opened by the U.S. Department of Justice sent shivers down the spines…of almost everybody. With the memory of the record fines paid by BNP Paribas and Deutsche Bank to American regulators still fresh, Moody’s downgraded in October long-term deposit and senior unsecured debt ratings of Danske Bank to A2 and maintained a negative outlook. As per the stock market, it didn’t have a much different view this time.

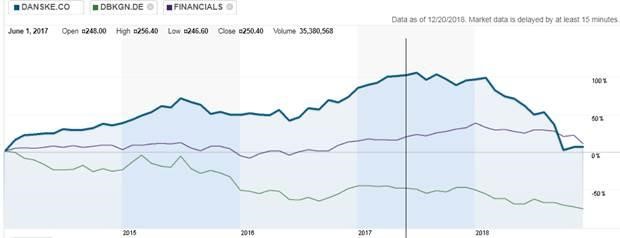

As can be seen in the chart below, financials (purple) progressed tidily in 2016/2017 while Danske Bank’s share recorded noticeable advances, even amid the uncovering of the Estonian business. However, things took a different path in 2018:

The bank’s share price suffered from large sell-offs of European stocks in February and October. But besides the systemic move, Danske was sold amid fears of a consequential fine, in a similar fashion as Deutsche Bank (plot in green). To sum up, both banks suffered greatly from their respective money-laundering scandals. It is worth noting that Deutsche dipped further (YTD -53%) as it also cleared a large part of Danske Estonian branch funds.

What Are Mirror Trades?

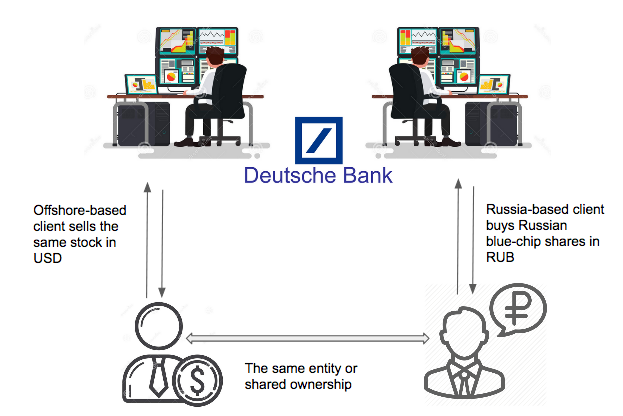

A legal but controversial investment strategy, they were behind a record penalty of more than €600 million inflicted by American and British regulators to Deutsche Bank. The latter was charged with lack of oversight regarding simultaneous buy and sell orders on the same stocks on different exchanges, as schematized below:

In a nutshell, the German bank’s traders did not question the nature of the trades, during low-profit times between 2011 and 2014, and thus helped Russian oligarchs smuggle money out of any control.

But if mirror trades are legal and can be used in arbitrage strategies, what is the exact problem with DB’s conduct? Provenance and denomination of funds. The bank’s trading desk in Moscow helped move an estimated equivalent of $6 billion out of Russia through mirror trades, while there were serious warnings:

- First, buyers and sellers made no profits on these trades.

- Second, end clients behind trade counterparts were not identified, which constitutes serious lacks in KYC and AML procedures.

We remind that in early 2017, Deutsche Bank cut performance-based bonuses in response to « financial impact of the settlement with the DoJ and our performance for the year. » and provisioned the penalties in their existing-litigation reserves.

Authorities estimated the size of funds to be near the €10 billion mark. If we are talking about Danske Bank today, it is because the funds it helped laundering are twentyfold larger.

What Lessons Should Banks Draw?

First of all, let us identify the key points that characterized the money-laundering schemes, executed within Danske Bank as well as Deutsche Bank:

While institutional corruption and conflict of interests were established as key violations in the Deutsche Bank case, this charge has not been established by Danish justice in the case of its biggest lender. Nonetheless, it may be envisioned as senior executives were aware of the non-compliance of the Estonian business prior to CEO opposition to the scale-back of non-resident business in this branch.

As per the other violations, for which the Danish prosecutor pressed charges, they consist of having insufficient knowledge about the Tallinn branch’s non-resident customers, failure to train local staff in AML practices as well as failure to integrate the same branch into the bank’s risk-management and control systems.

In the light of the violations listed above, we conclude that even well-established financial institutions fall to criminal schemes, with the (in-)direct involvement of senior management.This issue should be addressed by the development of an ethical culture within the firm, including small branches. This can also be achieved via the reinforcement of compliance role and the strengthening of internal control systems with powerful data-analysis tools (in this case, the detection of mirror trading patterns, among many possibilities). The same systems must be reviewed continually and tested on a regular basis.

A list of practical takeaways was developed by Denis O’Conor in his article [3] and is deemed valuable. From an accounting perspective, he notes that financial statements of clients must be analyzed in the light of the history of transactions conducted with the bank. While from a legal perspective, he believes that hiring an external auditing party allows the bank to maintain a certain level of objectivity in the case of fraud suspicion. Finally, he questions the regulatory reporting function within financial institutions and how much is needed before suspect activities are reported to local regulators.

Finally, given that the breaches were committed essentially in a “newly-acquired” branch, we stress that an independent audit by the acquiring firm of the acquired unit can be crucial to make sure of the soundness of its activities.

Resources

[1]http://cphpost.dk/news/business/danish-banks-in-gigantic-money-laundering-scandal.html

[2]https://www.ft.com/content/519ad6ae-bcd8-11e8-94b2-17176fbf93f5

[4]https://danskebank.com/about-us/corporate-governance/investigations-on-money-laundering